The theory of evolution took its very first steps on an island – and that is no coincidence. In 1835, during his journey to the Galápagos, Charles Darwin carefully observed finches. It was the differences in the shape of their beaks from one island to another that put him on the trail of evolutionary mechanisms (read the key to understanding Darwinian evolution).

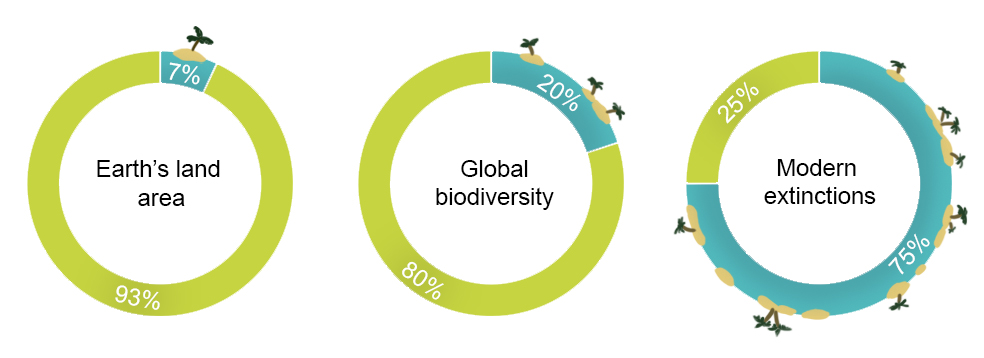

Islands are true jewels of biodiversity. Their geographic isolation, combined with unique ecological conditions, encourages the emergence of unique, often endemic species. That is why, although they cover only 7% of Earth’s land area, islands host nearly 20% of global biodiversity. This richness also comes with extreme vulnerability: three-quarters of recorded modern extinctions have occurred on islands.

Key percentage comparisons between islands (blue) and continents (green). Sources detailed in Fernández-Palacios et al. 2021.

This contrast between exceptional biodiversity and extreme vulnerability is precisely what the FRB-CESAB RIVAGE group explores, proposing a specific framework for assessing island ecosystems (Bellard et al. 2025). But before diving deeper, let’s take a moment to understand: How can islands, so rich in life, be so fragile?

The extraordinary biodiversity of islands is explained by their isolation, but it is precisely this trait that makes their ecosystems fragile. Scientists call this the “island syndrome.” Many island species have evolved in environments without certain predators or competitors, leading them to lose defenses that were no longer needed (think of the famous dodo of Mauritius or the kagu of New Caledonia, both birds that lost the ability to fly).

Small territories also mean small populations, which greatly limits genetic diversity and therefore their ability to adapt to disturbances. Finally, an isolated environment implies reduced mobility. When threatened, individuals cannot escape to safer territories.

Dodo of Mauritius (extinct) and kagu of New Caledonia (IUCN status: endangered). © Violette Silve.

On top of this intrinsic vulnerability, external pressures are intensifying:

- Climate change, including rising global temperatures and sea level rise — a particularly serious issue for islands,

- Land-use changes — from urbanization and intensive agriculture to tourism development — which further reduce and fragment available habitats,

- Growing human activity, leading to resource overexploitation and pollution,

- And finally, the intentional or accidental introduction of species from elsewhere. Predators, herbivores, or competitors disrupt ecological balances by preying on species that never developed — or lost — the ability to “resist.” These are called invasive alien species, causing biological invasions.

Biological invasions: a global threat to terrestrial vertebrates

In a study conducted just before the creation of the FRB-CESAB RIVAGE group (Marino et al. 2024), scientists cross-referenced data on 1,600 terrestrial animal species (birds, mammals, and reptiles) with those of 304 invasive alien species known to harm them. They estimated that at least 38% of Earth’s land area is already affected by these invasions — a figure likely underestimated, since the study considered only 10% of invasive species recorded worldwide.

But exposure does not necessarily mean danger. To refine their analysis, the scientists also considered how sensitive native species are to these threats. This approach allowed them to produce global maps of vulnerability to biological invasions. The result is clear: islands emerge as the most fragile zones, especially for bird populations. Some areas appear spared from invasions, but this may reflect gaps in data collection — a worrying blind spot for global biodiversity conservation.

And yet, even though island biodiversity plays a crucial role, it remains largely overlooked in global assessments, which tend to focus mainly on continents and climate. For instance, in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), only 1 of the 23 targets explicitly mentions islands as a conservation priority.

In this context, it has become urgent to better assess the vulnerability of island ecosystems. This is precisely the goal of the FRB-CESAB RIVAGE group, which proposes in its first article a brand-new evaluation framework specifically adapted to island biodiversity (Bellard et al. 2025).

This framework assesses vulnerability across three dimensions:

- Exposure: the degree to which species or their environments face pressures (in terms of intensity, scale, or frequency),

- Sensitivity: the extent to which species respond to pressures, depending on their biological and ecological traits,

- Adaptive capacity: their ability to adjust to new conditions through rapid ecological changes. For animals, this depends on mobility. For plants and immobile organisms, it relates more to persistence (e.g., high fertility and seed dispersal). Adaptive capacity can also depend on external factors such as habitat quality, availability, protection, or accessibility.

Overall biodiversity vulnerability can thus be defined as the sum of exposure and sensitivity, minus the adaptive capacity of species.

Unlike other approaches, which often consider just one pressure at a time (most commonly climate change, or more recently biological invasions with Marino et al. 2024), the framework proposed by RIVAGE integrates multiple pressures simultaneously, factoring in their intensity and scale, while also accounting for species-specific traits and adaptive capacity. This tool complements broader indicators, such as the percentage of species threatened on the IUCN Red List. The aim is not to reproduce the same results, but to highlight differences between approaches, refine analyses, and guide action where it is most urgently needed. A detailed comparison between the RIVAGE index and existing indicators is presented in their upcoming article, already available as a preprint (Marino et al. in review).

By proposing this index adapted to the specificities of island ecosystems, the scientists of the RIVAGE group are calling for action to put islands at the heart of conservation priorities.

Learn more about the FRB-CESAB RIVAGE group:

![[CALL FOR TENDER] the appointment of a service provider to carry out a literature review on the impacts of European seafood production-consumption chains on biodiversity and society](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/LogoFRB_RVB-Web_72DPI.png)

![[FRB-CESAB] FISHGLOB: Fish biodiversity facing global change – 2024](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/FRB-Cesab-Fishglob-conference-carremini.png)

![[Press release] Blue Justice: a new movement in favor of coastal communities, often excluded from decisions in conservation](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Photo_Blue_Justice_web2.jpg)

![[Press release] A better protection of marine megafauna through social networks and artificial intelligence](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Dugong©Julien-Willem.-Wikimedia-commons_web.jpeg)

![[Press release] Study in Nature: Protecting the Ocean Delivers a Comprehensive Solution for Climate, Fishing and Biodiversity](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Photo_CP_web.png)

![[Call for proposals] The FRB-CESAB call on systematic reviews has been extended until the 9th of September](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/aap-revue-systematique.jpg)

![[FRB-CESAB] Challenges and opportunities in large-scale conservation](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Cesab-Pelagic_Affiche-ENG.jpg)