À quelques jours de sa 11e plénière et de la sortie de 2 nouveaux rapports : l’Ipbes !

![[Biodiversité, une coordination européenne et internationale] (Re)découvrez l’Ipbes](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ipbes-11.png)

À quelques jours de sa 11e plénière et de la sortie de 2 nouveaux rapports : l’Ipbes !

To address this knowledge gap, a group of international researchers, including several members of the Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), have been working together for several years within the FRB’s Cesab (Center for the Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity). In May 2024, they published a major study in One Earth, drawing on nearly 650 scientific articles. They provide a better understanding of what works best, for humans and for nature, and call for a profound change in favour of social justice and equitable governance.

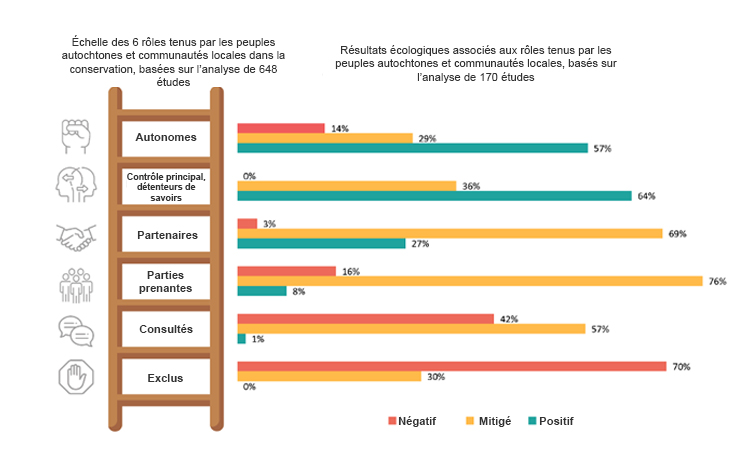

By examining 648 studies, the team first identified six ways in which Indigenous Peoples and local communities are involved in conservation and ranked them on a scale, from exclusion to partnership to autonomy. They then looked at the 170 studies highlighting the links between those six roles and the success or failure of projects (see figure below). The results are clear:

When Indigenous Peoples and local communities are excluded or involved only as participants or stakeholders, they may find themselves unable to influence decisions of great importance to their daily lives, may have their rights violated, or be denied access to lands of cultural importance, etc. In those cases, the big majority of ecological results are sub-optimal or even counter-productive.

In contrast, as one moves up the ladder and equal partnerships are established with conservation authorities, with greater control and cultural recognition for the communities, ecological success goes hand in hand with this recognition. Communities can experience respect for their values, rights, identity and culture, empowerment, cooperation and trust, all of which enable them to connect with and be stewards of nature and the land, while improving their quality of life, both individually and collectively.

Figure : The role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in conservation projects and associated ecological results.

According to the authors, empowering Indigenous Peoples and local communities as partners and leaders is now essential for fair and effective conservation in order to achieve the objectives of the Global Biodiversity Framework. Although transforming the strategic approaches, design, capacities, processes and interactions, financing and implementation of conservation processes will take time, they highlight various existing and interesting initiatives, such as the growing inclusion of territories and areas conserved by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (ICCAs), also known as territories of life.

<<

A collaborative effort based on rights and justice is needed to achieve a transformative change. This applies to all initiatives to conserve species and habitats, including the emerging wave of initiatives aiming to achieve the 30% by 2030 conservation target, and to restore the world’s degraded landscapes.

>>

Over the past three decades, biodiversity conservation has expanded, from a focus on nature preservation alone, to more ‘people-friendly’ approaches integrating objectives for both conservation and human well-being, as visible in the governance of protected areas and other conservation measures worldwide. However, integrated approaches have not necessarily led to benefits to local people, giving rise to a further shift from a focus on economic development, to one on social justice. This FRB-CESAB research project called JUSTCONSERVATION analyzed how justice concerns find support and integration in biodiversity conservation; a research need which is currently under-addressed. It asks:

This document summarizes in a few pages the group’s context and objectives, the methods and approaches used, the main findings, as well as the impact for science, society, and both public and private decision-making.

![[Press release] A new method to assess ecosystem vulnerability and protect biodiversity](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/FRB_cesab_CP_low_res.jpg)

As states committed to creating protected areas on at least 30% of their land and sea territories by 2030, an international team of researchers has developed a new tool to quantify the vulnerability of species communities. Combined with future ecosystem risk assessment studies, this tool should help decision-makers identify management priorities and guide protection efforts where they are most needed. Setting appropriate conservation strategies is a challenging goal, especially because of the complexity of threats and responses from species, and budget limitations. To overcome this challenge, the team of scientists, including researchers from CNRS, IFREMER, IRD and international organizations, has simulated the response of species communities to a wide range of disturbances, providing a robust estimation of their vulnerability, in a world where future threats are diverse and difficult to predict.

Quantifying the vulnerability of biodiversity is crucial to safeguard the most threatened ecosystems. Published in Nature Communications on the 1st of September 2022, this new tool stands out from previous work as it estimates the degree to which functional diversity, that is biodiversity and associated ecosystem functions, is likely to change when exposed to multiple pressures. It was developed as part of two projects funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) within its Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB) and with the support of Electricité de France (EDF) and France Filière Pêche (FFP).

Within the European Union (EU), agriculture is the subject of a long-standing, well-established and well-known common policy with the largest budget (386.6 billion euros for the period 2021-2027, i.e. 32% of the European budget). It is also affected by the internal market policy. In addition, various EU environmental directives apply to agricultural land. This is the case for biodiversity (Birds Directive, Habitats Directive, Environmental Liability Directive), environmental assessment (Projects Directive, Plans and Programmes Directive), water (Water Framework Directive, Nitrates Directive, Sewage Sludge Directive, Floods Directive, etc.). The EU is also party to several international conventions in the field of biodiversity that concern agricultural land (Convention on Biological Diversity, Bern Convention, Bonn Convention, Ramsar Convention, etc.).

Although European agriculture is subject to this threefold harmonization process, the rules for taxing agricultural land seem to differ quite a lot from one state to another. However, taxation affects several aspects of agricultural and environmental policies. It can encourage or discourage the profitability of agriculture, encourage the practice of a particular type of agriculture that is more or less favorable to biodiversity, and encourage or discourage a change in the use of agricultural land. Taxation of agricultural land therefore has multiple effects, both on the agricultural land itself and on agricultural, land use, urban planning and environmental policies. Moreover, within the debates on possible biodiversity policy strategies, the taxation of agricultural land and its modalities may favor one option or another.

For these different reasons, a comparative analysis of the taxation of agricultural land in Europe seemed useful to the French Foundation for Biodiversity Research.

The note is available in the downloadable resources section.

This report provides scientific insight into the elements under discussion within the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

It considers the draft framework in its official version of July 2021. The relevance of the four strategic goals, 21 action targets and associated indicators is examined in the light of the latest scientific work. This document was prepared by the French Foundation for Biodiversity Research (FRB) at the request of the Foreign Affairs Ministry.

![[Press release] Stewardship by Indigenous and local communities is the key to successful nature conservation](https://preprod.fondationbiodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CP_JustConservation_Web.jpg)

In the run-up to the 15th United Nations Conference on Biodiversity, several States have committed to creating protected areas on at least 30% of their land and sea territories by 2030. This tendency to focus on the proportion of land and sea to be protected in order to preserve biodiversity obscures more fundamental questions: how conservation is done, by whom and with what outcomes. These questions are crucial for effective biodiversity conservation.

Lead author, Dr Neil Dawson of University of East Anglia (UEA) School of International Development, was part of an international team conducting a systematic review that found conservation success is “the exception rather than the rule” – but research suggests the answer could be equitable conservation, which empowers and supports the environmental stewardship of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. This global review of evidence takes advantage of a growing number of studies looking at how governance – the arrangements and decision making behind conservation efforts – affects both nature and the well-being of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The work is part of the JustConservation research project funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) within its Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), and was initiated through the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy (IUCN CEESP). It is the result of collaboration between 17 scientists, including researchers from the European School of Political and Social Sciences (ESPOL) at the Catholic University of Lille and the University of East Anglia. The findings are published on 02/09/2021 in the journal Ecology and Society.

Dr Dawson said: “This study shows it is time to focus on who conserves nature and how, instead of what percentage of the Earth to fence off. Conservation led by Indigenous Peoples and local communities, based on their own knowledge and tenure systems, is far more likely to deliver positive outcomes for nature. In fact, conservation very often fails because it excludes and undervalues local knowledge and this often infringes on rights and cultural diversity along the way.”

International conservation organisations and governments often lead the charge on conservation projects, excluding or controlling local practices, most prominently through strict protected areas. The study recommends Indigenous Peoples and local communities need to be at the helm of conservation efforts, with appropriate support from outside, including policies and laws that recognise their knowledge systems. “Furthermore, it is imperative to shift to this approach without delay” Dr Dawson said. “Current policy negotiations, especially the forthcoming UN climate and biodiversity summits, must embrace and be accountable for ensuring the central role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in mainstream climate and conservation programs. Otherwise, they will likely set in stone another decade of well-meaning practices that result in both ecological decline and social harms. Whether for tiger reserves in India, coastal communities in Brazil or wildflower meadows in the UK, the evidence shows that the same basis for successful conservation through stewardship holds true. Currently, this is not the way mainstream conservation efforts work.”

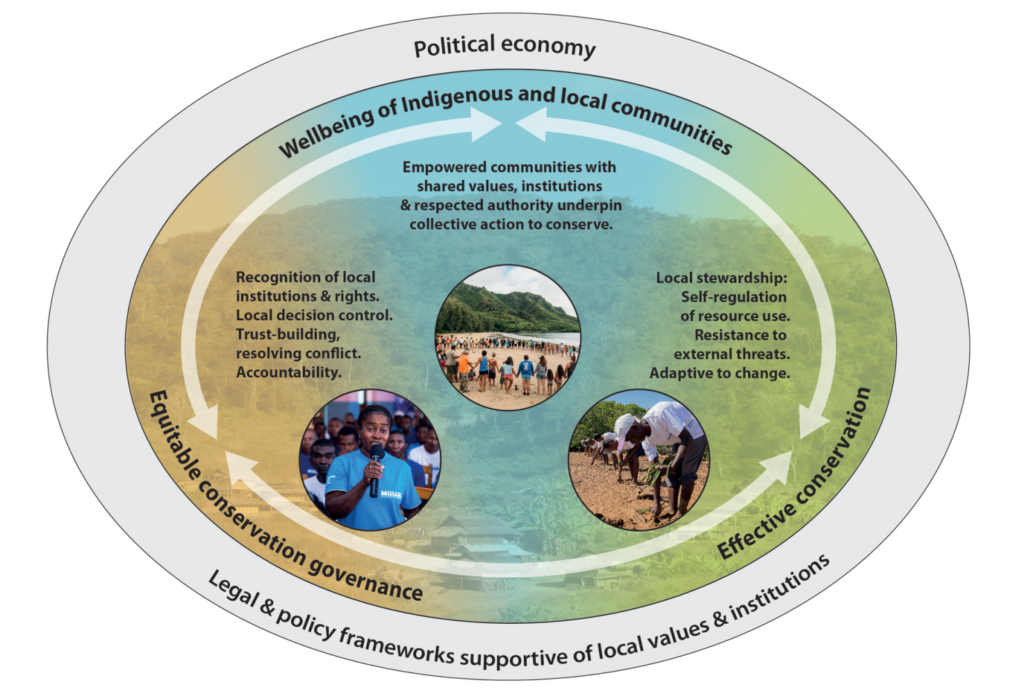

From an initial pool of over 3,000 publications, 169 were found to provide detailed evidence of both the social and ecological sides of conservation. Strikingly, the authors found that 56 per cent of the studies investigating conservation under ‘local’ control reported positive outcomes for both human well-being and conservation. For ‘externally’ controlled conservation, only 16 per cent reported positive outcomes and more than a third of cases resulted in ineffective conservation and negative social outcomes, in large part due to the conflicts arising with local communities.

However, simply granting control to local communities does not automatically guarantee conservation success. Local institutions are every bit as complex as the ecosystems they govern, and this review highlights that a number of factors must align to realize successful stewardship. Community cohesion, shared knowledge and values, social inclusion, effective leadership and legitimate authority are important ingredients that are often disrupted through processes of globalisation, modernisation or insecurity, and can take many years to re-establish. Additionally, factors beyond the local community can greatly impede local stewardship, such as laws and policies that discriminate against local customs and systems in favour of commercial activities. Moving towards more equitable and effective conservation can therefore be seen as a continuous and collaborative process.

Dr Dawson said: “Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ knowledge systems and actions are the main resource that can generate successful conservation. To try to override them is counterproductive, but it continues, and the current international policy negotiations and resulting pledges to greatly increase the global area of land and sea set aside for conservation are neglecting this key point. Conservation strategies need to change, to recognize that the most important factor in achieving positive conservation outcomes is not the level of restrictions or magnitude of benefits provided to local communities, but rather recognising local cultural practices and decision-making. It is imperative to shift now towards an era of conservation through stewardship.”

Figure: The central and inseparable role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in equitable and effective biodiversity conservation

The 15th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) will be held in China at the end of 2020. Countries member of the convention will be invited to announce specific commitments to biodiversity conservation.

It would be dramatic if the different states gathered on this occasion could only agree on a lower common denominator in terms of commitments and actions and if the decisions of the COP were not up to the challenge of the collapse of biodiversity.

States must commit to clear, precise, multiple and quantifiable actions, giving priority to the rapid and effective reduction of major pressure factors, while developing large-scale protection actions in order to rapidly safeguard what remains of biodiversity and restore its broad capacity for evolution.

Private stakeholders must also support this approach by working on reducing their sector-specific pressures on biodiversity.

Finally, citizens must be the driving force behind a major change in the way we consume, perceive and use biodiversity.

The two platforms of global scientific expertise, which are considering the future of biodiversity (IPBES) and of climate (IPCC), generally agree on the urgent need to quickly revise unsustainable production processes that aggravate both biodiversity erosion and climate change.

IPBES points out in its global assessment of the state of biodiversity presented in May 2019, that biodiversity is diminishing at an increasing rate, leading to the degradation of soil and ecosystem functioning. As a result, the services that humans receive from biodiversity are also declining rapidly, threatening the future of our societies. The direct drivers behind this degradation of biodiversity are well known and their respective importance has been assessed: land-use change at the expense of poorly humanized ecosystems and biotopes; exploitation, and often overexploitation, of marine and land resources; increasing chemical and physical pollution; climate change; and the multiplication of invasive alien species. All these drivers are aggravating each other and are also reinforced by indirect drivers: human population growth and the full range of socio-economic and political processes that lead to unsustainable consumption of the planet’s resources.

IPBES stresses the multiple negative impacts of intensive agricultural production systems on biodiversity, two excesses of which are now well documented. On the one hand, the excessive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers; and on the other hand, the increase in the production of plant-based proteins for animal feed which induces long-distance trade and relocates the negative impacts in regions with high biodiversity, such as tropical forests. Projections by 2050 show that without major lifestyle changes, the erosion of biodiversity and the loss of services that humans receive from the living world will continue.

Since the publication of the IPBES Global Assessment, the IPCC has produced a report on the links between climate change and land use, including through agricultural and forestry activities. The key messages of this report are consistent with those found in the IPBES assessment on land degradation and restoration published in 2018. The IPCC report highlights the importance of the contribution of the entire world food system to the production of greenhouse gases and recalls that changes in land cover, use and condition influence regional and global climates. It also recalls that climate change is a source of increased risks to the world food system and biodiversity, risks that will become even greater as food consumption, water needs and the consumption of multiple resources continue to increase. The IPCC calls for actions to adapt to and reduce climate change by highlighting the co-benefits that biodiversity can expect from them. The IPCC therefore calls for a sustainable management of soils and ecosystems as the only way to halt their degradation, maintain their productivity and contribute to the adaptation and the reduction of climate change. The IPCC emphasizes the need to reduce food waste and other waste while also accompanying the change in diets. Finally, the IPCC stresses the need to act quickly and to focus on the short term. It also highlights in its projections the need to increase forest areas.

In addition, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the third of the Rio Conventions, was held in India in September 2019, calling for a halt to land degradation and for its restoration to preserve ecosystem functioning and services, and to enhance food security. In the New Delhi Declaration calling for investment in land conservation and for unlocking all opportunities for action, COP Desertification underlines the importance of taking into account land management solutions against global warming and for biodiversity conservation.

Finally, the New York Declaration on Forests initiative, initiated in 2014 by major research institutions, think-tanks and NGOs, noting the continuing deforestation, particularly of tropical rainforests, solemnly called for the protection and restoration of the world’s forests to preserve their biodiversity and carbon sequestration capacity, thus joining the COPs in their call for governments to engage in systemic change.

In all cases, the findings of these bodies relay the warnings made by scientists over a long period of time, and their recommendations have been acknowledged or endorsed by a majority of countries around the world. Therefore governments cannot say that the warning has not been given and that the urgency of the necessary actions in favor of biodiversity has not been highlighted. Some countries quickly made commitments, such as France which announced a significant increase in the area of national protected areas, a major initiative, but which only partially meets the needs for essential actions, particularly in the short term.

However, significant differences of opinion persist when it comes to strategies and options to restore biodiversity or to mitigate climate change.

This is the case, for example, of the inclusion of the large development of energy crop areas in the IPCC scenarios, which, on a large scale, would have a major negative impact on biodiversity – and to which IPBES drew the attention of decision-makers. The same applies to the development of BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage) energy technologies or the development of intensive afforestation strategies. It is on these topics that exchanges between climate and biodiversity experts on one hand and between the various international strategic and political coordination mechanisms (UN conventions and agencies) on the other hand should be the most significant. It is crucial to recall that the fight against climate change is not an end in itself, but an urgent and indispensable means to enable the living, human and non-human, to continue their pathways of life and evolution. The fight against climate change cannot therefore be implemented by worsening the biodiversity situation. More than ever, FRB’s slogan, “biodiversity and climate, same fight”, remains clearly relevant.

Beyond COP 15 Biodiversity, COP Desertification or the forthcoming COP Climate, the Conferences of the Parties of the three Rio Conventions must move forward together. It raises the question of the necessary global coordination of actions that are likely to put the planet on a pathway ensuring both the future of human populations and of all living beings on mainland, islands and in the seas, without simple, caricatural solutions and while respecting freedoms and cultural differences.

Facing global challenges, it is no longer possible to continue to think in silos: climate on one hand, biodiversity or desertification on the other, and to allow solutions to emerge that will be poor compromises, not allowing all the major global challenges to be addressed simultaneously and with the same level of priority.

Several alternatives are possible to make solutions recommended by international bodies relevant to all the major challenges we are facing:

In any case, it is becoming urgent to promote strong scientific consensus that can form the basis of ambitious international decisions going beyond sectoral visions and political divisions affecting our future and the future of all life forms.

Declines in marine predators intensified globally in the 1950’s, as industrial fleets targeted previously inaccessible populations of sharks, tunas, and billfishes. These spatially extensive fisheries continue to expand, while global catches continue to decline. Given the difficulty of managing these fisheries sustainably, large no-take Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have been proposed for halting and reversing these declines. These MPAs require knowledge of the critical habitats that maintain these predators and that are relatively immune from the effects of human disturbances. This crucial knowledge is currently severely limited since based primarily on species geographic distributions obtained through fishery catches that remain biased with untargeted species, unfished areas and deliberate underreporting.

Here, the FRB-CESAB PELAGIC project overcame this limitation by collecting the most up-to-date and complete information on the biogeography and habitat use of marine mammals, sharks and fishes.

This document summarizes in a few pages the group’s context and objectives, the methods and approaches used, the main findings, as well as the impact for science, society, and both public and private decision-making.

At the European level, biodiversity research projects can be funded through a range of tools, including the seventh framework programme for research and development (FP7) in which the “Environment” theme is recognized as a major source of funding. Indeed, the European Commission provides important funding support for a range of research projects encompassing several sub-activities, including biodiversity, as part of this FP7 “Environment” theme.

Biodiversity, a cross-disciplinary topic, not identified as such in the FP7 “Environment” theme

Within the FP7, biodiversity appears in various sub-activities: “Pressures on environment & climate”, “Marine environments”, “Sustainable management of resources”…, but there is not a unique and delimited entry point for funding biodiversity research. Consequently, assessing the results of FP7 funding for the research community working on biodiversity and associated issues is complex.

To overcome this difficulty, the FRB conducted the present study – downloadable from the resources below – based on the results of the projects submitted to the FP7. The main goal of the study is to assess the importance of biodiversity among the FP7 “Environment” theme, through the sub-activities identified. Temporal trends of funding are also assessed for the 2007-2010 period, and the relative performances of the participating countries are compared.